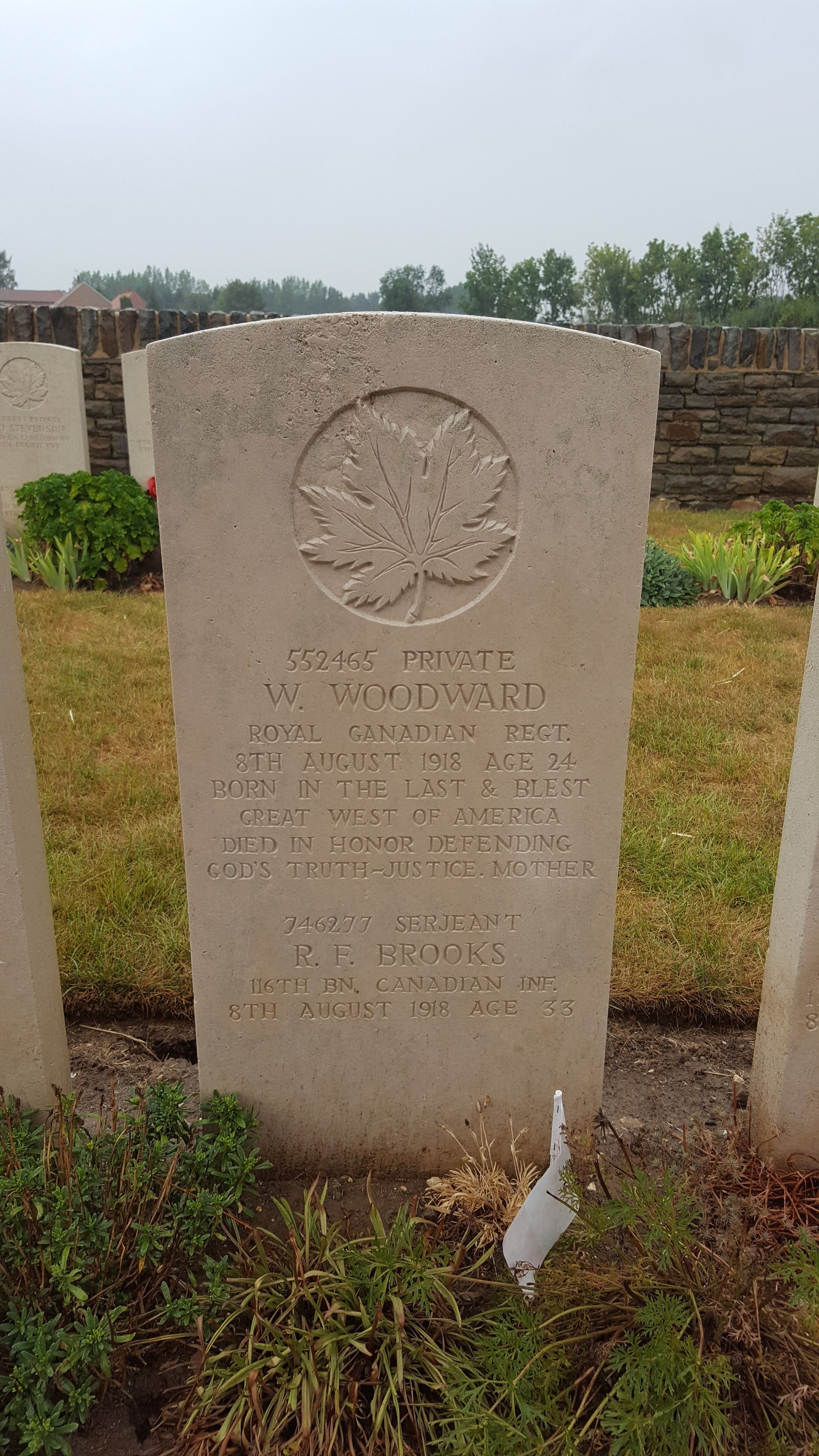

Lieutenant Wilfred Earl McKissock

Born 1890 in Owen Sound

Enlisted with 116th Battalion and served with 16thSquadron in the Royal Flying Corps

Killed in Action over Givency – June 2, 1917

Buried at La Chaudiere Military Cemetery, Lens France

Their decision was instantaneous. From the first time they sat down in the seat and reached for the controls, they knew they were never going to let it go. Sure, it was going to be a dangerous job, but it was ‘war’ and anything would have been better than having to endure the unbearable conditions of the mud of Flanders. Most of these men started out as ordinary Tommies…regular soldiers trudging up and down country lanes with a pack on their backs and a rifle over their shoulders. However, these men were different from the others. Whether it be during long marches with their platoons or practicing down at the range, the second they caught a glimpse of the majestic crafts flying above them it was love at first sight. From that day forward they would accept nothing but a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps.

This is a story of two men…two men who grew up in the same small town at the exact same time. One of the two was four years older than the other, however due to the relatively small population of the town and the fact that everyone knew everyone, they would surely have known of each other. The elder of the two was an elite athlete. He was a leader on the high school football team and excelled in many disciplines in track and field. But this man was not only well-known in the community, he was also an expert fencer…eventually rising to become the Dominion of Canada’s top fencing champion. After graduating from high school, he enrolled at Hamilton’s McMaster University in search of a higher level of education.

The second man of the pair was also born in and grew up in Owen Sound, Ontario. While not necessarily unathletic, he tended to avoid team sports. Instead of blocking, tackling or jib-jabbing others with an epee, this young man was actually a bit of an oddball…some might even say a loner. His social standing was not helped out when his parent’s enlisted him in Miss Pearl’s Dance Studio in an effort to teach him how to dance...however, in retrospect, the skills he gained in taking on swarms of bullies in the playground may have actually prepared him for life in the future. Akin to his personality, as he grew older he focused his attentions on more solitary activities like venturing off to hunt squirrels, rabbits or other varmints with his rifle. The corresponding skills at marksmanship and burning desire to attack those who sought to attack him would both pay dividends in the end. Apart from his academically gifted fellow Owen Sounder, this man was unapologetically uninterested in academics. However, once he completed his high school studies, he did enlist at the Royal Military College in Kingston, where finished second to last in his class in two out of his three years spent there.

A simple review of the background of these two men, may demonstrate that one was setting himself up for a successful career in whatever he put his mind to and the other might be affectionally categorized as a bit of a lackadaisical slacker. The key word in this statement most evidentially is the word ”simple”. Akin to the war’s unyielding draw, both men would be pulled into the service. They both started in the rank of Lieutenant and served in the infantry. However, both of these men would be drawn towards the air service and shortly after enlisting would seek a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps. It was at this instant where the relative trajectories of the two men would intersect, then dramatically be pulled apart. One of the men would eventually die in a blazing disaster, killed in one of his first battles. The other would become Canada’s most storied, respected and recognized airman and WW1 Ace Captain/Lt. Col./Air Marshall William “Billy” Avery Bishop, VC, CB, DSO & Bar, MC, DFC and ED.

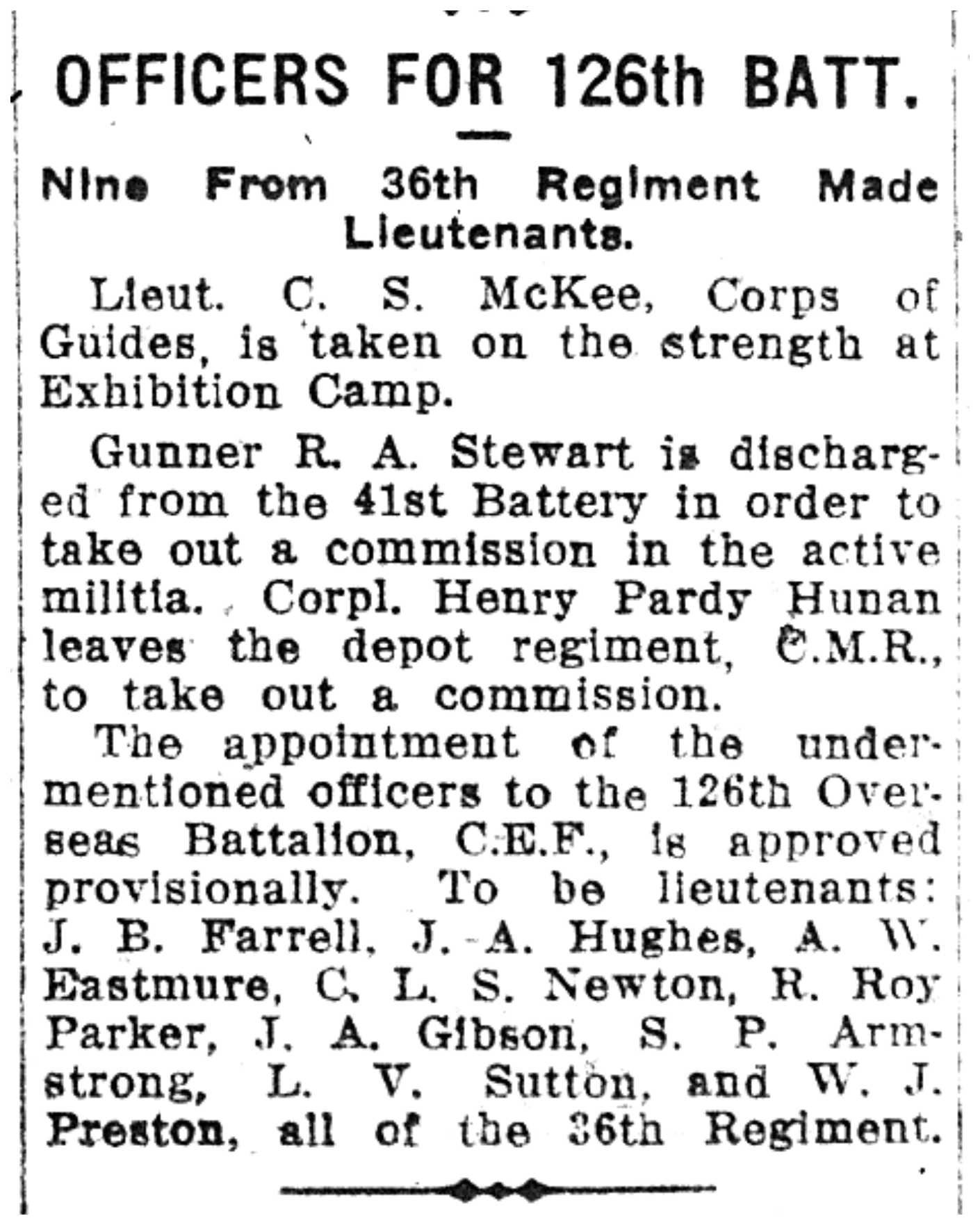

The first of the two men was 26 yr old Lieutenant Wilfred Earl McKissock. Like Bishop, Wilfred was born in the lakeside port city of Owen Sound. As detailed, he was an active young lad and participated in a wide range of sports and activities. Contemporary records show that he was also an excellent student, both in high school and in university, and extended his social interests to become an active member of the YMCA. A magazine produced by McMaster University in Hamilton in 1914/1915 showcases the great results he was able to achieve in both their Track and Field program and Football program. In the spring of 1916, McKissock elected to delay his completion of his University degree and joined Sam Sharpe’s 116thBattalion being raised in Uxbridge, ON. As a Lieutenant he was assigned to assist in the training of men at Camp Exhibition and Camp Borden. Akin to his personal interests and unique skillsets, he was responsible for training the men in both physical fitness and how to effectively use the bayonet. When the 116thdisembarked to England in July of 1916, McKissock was attached to their sister unit, the 182nd Battalion, then moved onto the 1stCentral Ontario Regiment. It was from this unit where he was sent overseas and arrived in Liverpool on the 26th of September 26th, 1916.

Throughout the fall and winter of 1916/1917, the CEF was busy reorganizing, replenishing the men in the battalions of the First, Second and Third Divisions. A steady stream of troops ships carrying soldiers raised from communities across the breadth of Canada arrived in England. In most cases, these battalions were broken up and their men redistributed to units already located oeverseas. The CEF was gearing up for the forthcoming assault on Vimy Ridge (as part of the Battle of Arras) and needed to ensure they battalions were well resourced with fit and well-trained men. It was during this time when Lieutenant McKissock requested to be transferred to the Royal Flying Corps.

He was accepted and on May 1st 1917 and was attached to the 16th Squadron the following week. This unit was stationed in the area just west of Vimy Ridge around Givency. He was attached to a unit responsible for Aerial Observation with orders to survey enemy troops movements, harass the German trench lines through rudimentary bombing runs or strafe any unfortunate chap (or group of chaps) who gathered in sectors of the trench visible from above. McKissock provided the following account from his first solo flight while stationed with the 16th Squadron.

“It was early morning, about 5 am, and after making various landings I went off to see a monument in the direction of the morning sun. I circled around it several times in the indescribable grey morning mist, and then feeling like a small boy in unfamiliar territory I returned to the aerodrome. Just as I was descending I saw a machine turn a neat somersault to the ground. I made a forced landing and strange that the forced landing was the best I had done to date. I ran over to the upset machine and found the pilot looking at his broken propeller. Nothing exciting had happened to him except that he had been upside down for a while with castor oil, which if the lubricant used for rotary engines flowing soothingly over him.“

The account was taken from a letter McKissock sent back home to his mother. It demonstrates that apart from being a weapon of war, that McKissock found it a really cool toy. It represented freedom, excitement, adventure, exploration. With his comments on how a fellow airman was able to conduct a virtual somersault upon landing, it demonstrated how dangerous these machines could be. The final comment regarding the castor oil drenching the pilot further alluded to another hidden risk posed by these new instruments of war. A keen observer may also notice what was not included in the letter. There was no mention of the use of the craft as a weapon of war. He also seemed to think first about the well being of his fellow airman. This showed that McKissock showcased an air of empathy…however, while he probably did not know it at the time, this was an attribute that did him no favours as a pilot in the RFC in 1917.

McKissock served within the 16th Squadron in the Spring of 1917. It was during these same months when the German Ace of Aces, Baron Manfred von Richthoven and his Flying Circus ruled the skies over the Western Front. It was estimated that during this phase of the war the 5 Allied planes would be knocked out of the sky for every German aircraft. It was under these rather hostile odds, that McKissock took to the skies. The records do not reveal if he was assigned to sections that actively hunted German planes. Rather, he seemed to be assigned to a unit that was responsible for observing enemy artillery positions. From the date he was assigned to the 16thSquadron to June 1st, 1917 he was not recorded as claiming any victory over an enemy craft. It was on that final fateful day, when McKissock took to the skies with his squadron. The casualty description indicates that around 11AM he was swarmed by a handful of German planes. They came out of nowhere and he probably didn’t even know what it him. The last view of McKissock’s plane was that it had been seen ablaze and careening towards the earth. It was within these circumstances, where Lieutenant Wilfred Earl McKissock met his death.

Acres of trees have been felled to satisfy the countless volumes of books, articles and columns written about Canada’s most well-known WW1 Ace. Thus, we do not need to devote more words of glory and adulation in his favour. Rather, there is one final story and circumstance which relates to the pair of Canadian heroes that should be related. McKissock was killed in a when upwards of four Germans planes attacked his craft on the 1stof June 1917. A mere 16 hours after McKissock was killed, Billy Bishop took to the air in the skies east of Vimy. It was 3AM...well before sun began to illuminate the horizon. Akin to those days of his youth where he would quietly stalk woodland critters, Bishop quietly set out on his own to bag himself some Germans. Bypassing the first aerodrome he came upon as it was still sound asleep, he ventured deeper into German territory until he located a second one. It was here where he saw seven airplanes being readied for takeoff. In that instant Billy pounced…and then he pounced again…and again and again…attacking each plane as it tried to take to the skies. One by one he fearlessly took on the enemy airplanes and one by one he knocked them out of the sky. By the time he made it back home, his plane was riddled with bullet holes and he had added four more wins to his growing tally…oh and from his courageous exploits he was rewarded the Victoria Cross.

In the years that followed the war, the citizens of Owen Sound would all gather to remember and mourn those who did not return home from the war. The surviving veterans would put on their uniforms and take that sombre march down to the town square. Amidst this crowd of soldiers, Owen Sound’s own William “Billy” Avery Bishop would most certainly take his place of honour amongst the others. As one might expect, the crowd of locals would fete their hometown hero and honour him with rounds of applause…however when the applause died down and the ceremony began, when the officiant began to recited the names of those men from the town of Owen Sound and surrounding areas who did not return home, with his hat in his hand and his hand on his heart, Billy Bishop, Canada's Ace of Aces would be thinking of his fellow airman, Lieutenant Wilfred Earl McKissock…the ‘good’ pilot who did not make it back.

Remember him.