Private Isaac Beauchamp

644654 (originally with the 157th Simcoe Foresters)

Born Penetanguishine Ontario

Killed in Action – Aug 30, 1917 Hill 70

Another rush of cold air aided in hustling the men into the line. Still, despite being bundled in their heavy winter weather gear the warm smiles shared amongst them were the key to easing the sharp chill in the air. It took dedicated and patriotic men to brave a cold February weather and trek into town and enlist with the 157th. Especially when the raising was taking place on the town situated at the edge of Georgian Bay, Penetanguishene. It was the winter of 1916 where from their offices in Collingwood, Orillia, Barrie, Midland, Coldwater, New Lowell and here in Penetanguishene, the 157th Simcoe Foresters signed up men to join the cause and enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces.

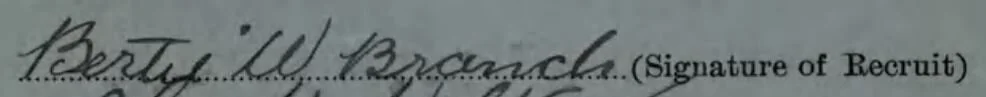

The day was February 10, 1916. 38 men put pen to paper and joined the ranks of the 157th. As they shuffled their way through the office, each man filled out the requisite forms which were then was authorized by local Lieutenant John Hogg and the Lieutenant Colonel of the newly formed unit, Lt. Col David Henry MacLaren. The battalion MO then conducted checks on all the men, measuring their height, chest size, and recording down their particulars. The collection of recruits included a number of recognizable faces. Frank Anderson, Frank Cadieux, the Piette brothers, Ralph McColl and Ernest Sweet. Then there were Napoleon and Joseph Picotte. And the other Napoleon, Dault. The there was Isaac. Isaac Beauchamp.

At 21 years of age, Isaac joined up with his mates to ensure he did not miss the big show. They all did. All the guys wanted to ensure that they would join in on the fun. Thus, he followed his friends (new and old) to Camp Borden to train. The men completed their basic training in the Spring and Summer of 1916 before setting off to England in the Fall. They arrived in England on Oct 28th and to their collective disappointment, the battalion was broken up and distributed to other battalions for service in France. Thankfully a significant allotment of the men was sent to one battalion being readied for war in Flanders. It was the 116th Battalion. Isaac Beauchamp was now an Umpty-Ump.

I will jump forward to the circumstances of his death…all of which are scarce and limited. No individual picture exists of the man…at least not one of his face. He is one of the soldiers pictured in a group photograph of the 157th Simcoe Foresters…maybe? While he is buried at the Aix-Noulette Communal Cemetery near Lens, online pictures of his gravestone have yet to be posted. Even the circumstances of his death are vague. The official record merely shows that he was KILLED IN ACTION. The Battalion Diary states “Working parties were supplied for trench digging, etc. in the forward area. Casualties, 2 other ranks killed, 6 other ranks wounded. “ This provides little material to help gain a better insight into the man who gave it his all. Yet a little digging into accounts of the battalion’s history at Hill 70 can provide more colour to his sacrifice.

Between August 18th to the 25th 1917, the CEF embarked on the second largest attack in Canadian history. The attack at Hill 70 was only surpassed in size and scope by the one held at Vimy Ridge. 9,198 Canadian soldiers were killed, wounded or declared missing in the battle of Hill 70. The 116th joined the fray on August 22nd. On the 21st the planned Canadian attack was pre-empted by something totally unexpected. While the men waited in their trenches for the sound of the whistle, the Germans were prepared…more than prepared. They were going to attack the Canucks first! Before the planned jump-off time of 4:38am, the Germans sprung out of their trenches and rushed the Canadians in their trenches first. With the glint of their bayonets occasionally reflecting the light from a towering flare, they sprinted forward upon the unexpecting men. The 27th and 29th Battalions were forced to engage in hand to hand combat from the initiation of combat and the battle which proceeded throughout the day. In their sector, the day’s tally amounted to 7 officers and 58 OR killed with the 29th Battalion along with another 50 men missing and 183 men wounded. Beside them in the 27th Battalion saw 35 men killed, 14 missing and a colossal 248 men wounded. It was a bloodbath.

This horrendous death toll to necessitate calling the still green 116th to relieve the spent 27th on the 22nd of August. Over the next week, 22 additional men from the 116th would fall trying to retain the hard-won positions in the forward trenches. Yet, to be accurate, they were not really trenches. The 27th followed by the 116th were tasked with holding a part of the battlefield which would be more resemble Berlin in WW2 than Vimy or the Somme. They were responsible for the area on the edge of the key city of Lens. Instead of trenches carved out of farm fields they face a demolished, ruined city with piles of bricks and destroyed sections of buildings serving as protection for the men. It was here that the Canadians were tasked with holding onto territory just gained from the Germans. While the Germans moved back on the 25th, they continued to bombard the area now held by the 116th. It was on the final day of their stint at the front, the 31st of August, where somewhere, out there, at a time that was never documented, Isaac Beauchamp’s war would come to an end. Let us remember him.

Lest we forget.