Sergeant Earnest Henderson

690078

Born Lindens, ON (Hamilton)

Killed in Action on Sept 29, 1918 in the Battle of Canal du Nord at Cambrai

Buried at Ste. Olle British Cemetery, Raillencourt, France

The wail cascading from across the distance instinctively caused his toes to rhythmically tap along. His well-tuned ear easily recognized the familiar song, the pipers' ballad commemorating the clan’s loyal backing of the crown against the Jacobites in 1715. It was The Campbell’s are Coming…used by highlander battalions when marching into battle for over 150 years. For Earnest Henderson, it was the song adopted by his adopted battalion the 173rd Highlanders, the Argyle and Sutherland (Prince Louise) Battalion from Hamilton, Ontario. And for the proud Scottish-Canadian he it would straighten his back and bolster his spirit before leading his men over the top.

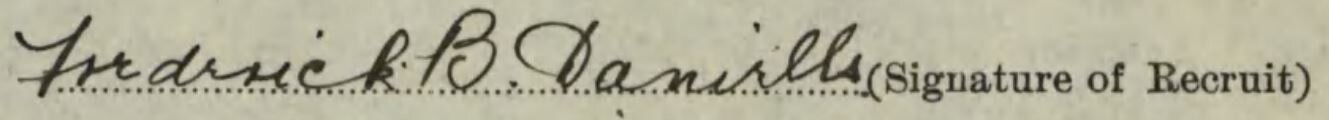

Henderson enlisted in the war in Feb of 1916 at the age of 29. He was a respected citizen working as a Grocer and attending lodge in town as a Freemason. With 12 years serving with the 91st Argyllshire Highlanders prior to the Great War it was expected that he enlist when the call was made. Thus, he left his wife May at home in Hamilton and went off to war. Upon joining the 173rd he was quickly promoted to Sergeant and transferred to the 2nd Reserve and 8th Reserve Battalion before joining the 116th on August 18th, 1918. This coincided with the time that the 116th ‘s ranks were bolstered by an influx of replacements and conscripts.

Despite serving in reserve battalions for over 2 years, he was able to manage to avoid any serious injuries other than the odd bout of influenza and appendicitis. His luck did run out when on the 29th of September in 1918 when the 116th was decimated on the approach into Cambrai in the midst of the 100 Day Push. 94 men of the 116th would fall on that fateful day, including the Sergeant from the Hamilton, Earnest Henderson.

Lest we forget.